Earlier this month, the renowned dance photographer Avinash Pasricha was in Bangalore for a workshop and exhibition organised by local Odissi dancer Kshama Rau. Over the past fifty years, Avinash Pasricha has captured images of almost all of India’s greatest musicians and dancers. He has contributed his photographs to several books on dance, often in collaboration with dance historians Sunil Kothari and Leela Venkataraman.

Earlier this month, the renowned dance photographer Avinash Pasricha was in Bangalore for a workshop and exhibition organised by local Odissi dancer Kshama Rau. Over the past fifty years, Avinash Pasricha has captured images of almost all of India’s greatest musicians and dancers. He has contributed his photographs to several books on dance, often in collaboration with dance historians Sunil Kothari and Leela Venkataraman. As an admirer of his work, I didn’t want to miss the interactive session with the photographer on June 4th at the Alliance Française. We were a small group of photographers and dance enthusiasts. He began his talk by saying that photography cannot be taught. He told us how he began taking pictures and became a dance photographer. He also showed us a film on his life which was made 19 years ago. It was a collection of his photographs with his own voice narrating his career as a photographer. We also watched a short video which included a superb series of images of Odissi dancer Madhavi Mudgal set to music. Finally, he shared several aspects of his journey as a photographer with us…

As an admirer of his work, I didn’t want to miss the interactive session with the photographer on June 4th at the Alliance Française. We were a small group of photographers and dance enthusiasts. He began his talk by saying that photography cannot be taught. He told us how he began taking pictures and became a dance photographer. He also showed us a film on his life which was made 19 years ago. It was a collection of his photographs with his own voice narrating his career as a photographer. We also watched a short video which included a superb series of images of Odissi dancer Madhavi Mudgal set to music. Finally, he shared several aspects of his journey as a photographer with us…On how he became a photographer…

My father was a portrait photographer. I grew up in his studio. I would watch him at work. It was an interesting experience to see the old method of photography. At that time, the photographs were hand-painted afterwards. I enjoyed sitting in the shop and attending to customers. When I was in school, I was also a businessman. I used to sell prints to my classmates. A print cost 4 annas and I used to sell it for 8! That was business. The plan was that I would take over my father’s shop. But there’s a guy upstairs who decides what’s good for you, and that’s what happened. From 1957 I learnt darkroom on the job. Later I heard about a new magazine starting called SPAN. And I became the photo editor. And that journey made a photographer out of me.

At the time I used a Roleiflex camera and I worked in black and white. The printing process was complicated. The blocks were made in Calcutta and the printer was in Bombay. And Indian Airlines coordinated the rest.

At the time I used a Roleiflex camera and I worked in black and white. The printing process was complicated. The blocks were made in Calcutta and the printer was in Bombay. And Indian Airlines coordinated the rest.I became known as a photographer when I started working for SPAN. I was with SPAN from 1960 to 1997. I’d been on many assignments. The writer collects all the materials and has ample time to write the story but as the photographer you have to think fast… you have to think ‘Where is the story?’ and capture it. As a photojournalist you’re constantly looking for pictures, pictures with a purpose. I developed an approach to people and situations. Each picture must tell a story. After all, a picture tells a story without words. If I’m able to produce that picture then I think I’ve done my job.

My father was a photographer, I followed in his footsteps, and now so does my son. It makes me feel proud. My son Amit Pasricha is a better photographer than me.

About dance photography…

My first dance pictures were pretty bad. They were of Indrani Rahman. They went green because the ektachrome process turned pictures green because of the chemicals. I still have them. There was no telephoto so the photo was always small no matter how close you got.

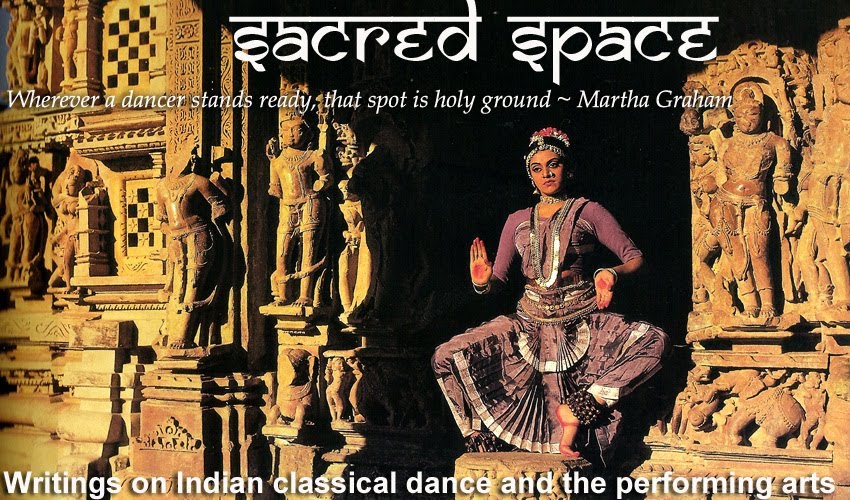

A lot of people shoot dancers as a statue. They get in a pose and shoot. In fact a lot of people today still shoot like that… as a statue in all her finery. All they think of is the beauty of the costume and jewellery but not the dance. You have to see where the dance is. For me, dance is in the eyes – if you can capture it, then you’re a dance photographer. Only 10% of the time or even less, there’s an expression. By the time you see the expression and you click, it’s gone. (Left: Bharata Natyam dancer Malavika Sarukkai)

A lot of people shoot dancers as a statue. They get in a pose and shoot. In fact a lot of people today still shoot like that… as a statue in all her finery. All they think of is the beauty of the costume and jewellery but not the dance. You have to see where the dance is. For me, dance is in the eyes – if you can capture it, then you’re a dance photographer. Only 10% of the time or even less, there’s an expression. By the time you see the expression and you click, it’s gone. (Left: Bharata Natyam dancer Malavika Sarukkai)In studio photography the dancer stays in one spot and the photographer moves around the dancer. In the theatre, I sit in a seat and watch the dancer dance. In the studio, I dance around the dancer! I’m constantly interacting with the dancer… trying to make her think that she’s dancing. So I say “There’s a tree. A bird. Krishna,” to get her mind away. “Look there! There!” I do it very fast. I tell her to look here and there very quickly so she has no time to think and become self-conscious. Otherwise the mind is always thinking ‘Where is my foot?’ ‘Is my hand in the right position?’ …Otherwise the guru is always there.

In the theatre you never know what the lighting will be like and what will come next. Fortunately in Indian classical dance many things are repeated so you can anticipate. So I’ve learnt to anticipate repetition. (Right: Kuchipudi guru Vempati Chinna Satyam)

In the theatre you never know what the lighting will be like and what will come next. Fortunately in Indian classical dance many things are repeated so you can anticipate. So I’ve learnt to anticipate repetition. (Right: Kuchipudi guru Vempati Chinna Satyam)Sometimes I’m invited to a dance performance and people are surprised when I don’t show up with my camera. When you’re a photographer, you’re expected to do it every day!

How he started taking pictures of dance…

While I was working at SPAN as a photographer, one of my cousins was into music. He would go to all-night Hindustani music concerts and festivals. I was experimenting those days with black and white triads. So I went with him to concerts. I went there but I had no ear for music. I tried to capture the mood with my camera. At the time I didn’t care about disturbing the artist while I shot and some of my best pictures were taken at that time. And it hasn’t happened since… because now I’m too conscious wondering if I’m disturbing the artist or the audience. And pictures didn’t matter that much at the time when I was experimenting... from there I moved to dance.

I’m over attached to dance. I don’t know how to detach myself. Sometimes I feel stuck. I tend to do the same thing. Even one of the dancers had remarked that my lighting is always the same. A lot of people have copied my lighting. Sometimes I can’t even tell if a picture is mine or somebody else’s! A few years ago one could tell because there was a standard lighting used. But a dancer once made a funny comment: all you need to do is change the face. [He laughs.] I need to grow to get out of that. Fortunately some of the younger photographers are doing things differently… without make-up, in the forest, plain pictures… and there are magazines that now publish those. The point I’m trying to make is that one needs to get out of the rut. You tend to get in a rut and should ask yourself how to get out of it. And now at the age of 75, it’s more difficult. Partly because people who come to me have a certain expectation. They want the kind of pictures I’ve been taking for all these years. So am I going to satisfy their need? Or am I going to satisfy my inner need, my urge to shoot things differently? Is it possible to satisfy both?

I probably produce only one great picture every five years. Not much more than that. One was a portrait of MS Subbulakshmi singing. It was pure luck. I feel that the picture captured that moment of devotion on her face for which she was famous for. I can show you pictures of Pandit Jasraj that I shot in the 1960s and last year and give you a kind of pictorial biography without saying any words whatsoever. Also Shivkumar Sharma and Bhimsen Joshi…

On digital photography…

I feel digital photography fails in recording dance. It’s too slow. By the time it records the image, the dancer has moved. You may miss moments. After a performance of 1.5 hours I may get a few decent pictures.

Another thing that would be taught in the early days would be to take monuments from a distance… it’s a learning process to use aperture to get enough depth when you need depth. You learn this yourself or someone teaches you. One advantage of digital is you don’t run out of film. Sometimes I would finish one or two rolls of film and then something more interesting would happen! So what’s good with digital photography is you don’t run out of film. But you’re left with too many pictures in the end! It takes time to choose and edit them. Editing is a headache. My computer is full and I have to put images on a backup. There are too many to look at! (Left: Kuchipudi dancer Sobha Naidu)

Another thing that would be taught in the early days would be to take monuments from a distance… it’s a learning process to use aperture to get enough depth when you need depth. You learn this yourself or someone teaches you. One advantage of digital is you don’t run out of film. Sometimes I would finish one or two rolls of film and then something more interesting would happen! So what’s good with digital photography is you don’t run out of film. But you’re left with too many pictures in the end! It takes time to choose and edit them. Editing is a headache. My computer is full and I have to put images on a backup. There are too many to look at! (Left: Kuchipudi dancer Sobha Naidu)On the photographer’s eye…

I’m a very bad street photographer. Also, I don’t shoot negative pictures ever. Because my whole grounding was in SPAN and we had to always show positive pictures. Once we printed some pictures of an American working in eastern India and there were some children watching him work. A child watching had a torn shirt. The editor said that we can’t show negative pictures. There was nothing negative, just a man working and some children watching… but the child’s shirt was torn. There are different ways of looking and seeing.

I may have shot 100,000 pictures. Very often I’m clicking a picture in my mind without a camera. I see a picture, I stop and take it. It’s gone but it stays in your mind even though you don’t have it on film. There are so many missed pictures in your life.

I may have shot 100,000 pictures. Very often I’m clicking a picture in my mind without a camera. I see a picture, I stop and take it. It’s gone but it stays in your mind even though you don’t have it on film. There are so many missed pictures in your life.Each one sees differently. What you see and I see is different. My theory after over 55 years of photography is I can learn and continue to learn but I can’t teach others how to see. See for yourself. You can learn by looking: this is good, this is bad, I can do it differently. (Right: Sattriya dancer Anwesa Mahanta)

Then there’s the observation of light. How light falls. If I can’t change the light, then I can change my position. Or I can compose it differently. I can include or exclude. I have to compose my frame. With digital today you can see the image right away. But I feel that by constantly trying to see, you may miss the shot…

The other thing I’ve learnt is that when people come to you, half the time they don’t know what they want. So it becomes first your own understanding of what they really want and then making them understand. This is what would work for them. If they still don’t appreciate what you’re saying, then you shoot their way and your way and you choose.

Everyone sees differently. I have been doing photography for 55 years. I can continue to learn – it keeps me alive but I can’t teach it. You have to learn for yourself.