November 28, 2013

Dhimsa dance in the Araku Valley

Though the Araku Valley is supposed to be “one of the least spoiled and less commercialized tourist destinations in South India” (according to Wikipedia), the AP Tourism department did a good job of commercialising this one-day trip. Of course I couldn’t really expect more from a one-day organised trip, and my very tight schedule did not allow for more. But this was a convenient way to squeeze in a visit to the Araku Valley as well as the Borra Caves (which my editor was keen on featuring) where we stopped on our way back to Visakhapatnam.

After the obligatory visit to the Araku Tribal Museum, there was a demonstration of Dhimsa, the dance performed by the tribal communities of the Araku Valley. This is a ceremonial dance performed by women during festive occasions like weddings and important festivals. This organised demonstration outside the AP Tourism hotel was not the ideal context or setting to witness Dhimsa, but I appreciated the chance to see this tribal dance tradition which otherwise I would not have had the opportunity to see at all. I had only had glimpses of tribal dance in photographs, films and YouTube videos, and this was the first time I was seeing it ‘live’.

The women were dressed in brightly-coloured saris in tones of scarlet, magenta and fuchsia. Each had a flower elegantly pinned to her hair which was gathered in a bun at the nape of the neck. Almost all the women wore three nose rings, typical of the tribal women living in this region.

One thing which immediately struck me was the detached look the women had as they danced. They all had a very straight-faced and almost stern and even bored expression. This was quite a contrast to the wide sparkly grins of the Bharata Natyam dancers I’m used to seeing. Were they bored of this tourist office routine? Perhaps they were. Or maybe a smile is superfluous when it comes to this ceremonial dance.

The dancers were assembled in a row, one arm interlocked behind their backs, the hand of the other on the shoulder of the woman in front. The woman who led the row of dancers seemed older than the others and held a towel. The dancers moved in quick-paced rhythmical steps, making circular patterns moving clockwise in inward circles before changing direction and moving counter-clockwise, this time in outward circles. At times they formed a tight circle and swayed their bodies in unison inwards, before crouching down and shuffling forwards. Their anklets jingled as they danced.

I recently came across my photos taken during this demonstration of Dhimsa and thought I’d share them on this blog...

You can watch a clip of Dhimsa here:

September 5, 2013

Aditi Mangaldas premieres her latest production 'Within'

Aditi Mangaldas is one of the biggest names in Kathak today and needs no introduction to Indian dance enthusiasts. Known for her virtuosity and innovative choreography which takes a strong foundation in classical dance and blends it with a contemporary sensibility, combined with a refined aesthetic sense for stage and costume design, her productions have received critical acclaim across the world.

“Aditi Mangaldas Dance Company, the Drishtikon Dance Foundation has been established with a vision to look at tradition with a modern mind, to explore the past to create a new, imaginative future… we seek to challenge established norms and develop the courage to dance our own dance, while at the same time being informed about the heritage, cultures, influences and language of other dance styles and forms, viewpoints and ideas.”

(Images by Dinesh Khanna)

June 15, 2013

The last Mahari

February 11, 2013

The revival of dance as temple ritual

Last year I had the opportunity to travel to Hyderabad and witness the temple rituals performed in the Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple during its Brahmotsav celebrations. The experience was a very special and unique one because this is the only temple where dance is performed as part of worship today. In the following article I tell the story of how dancer Swapnasundari was able to reinstate and perform the ritual dances of Vilasini Natyam in this small temple on the outskirts of Hyderabad.

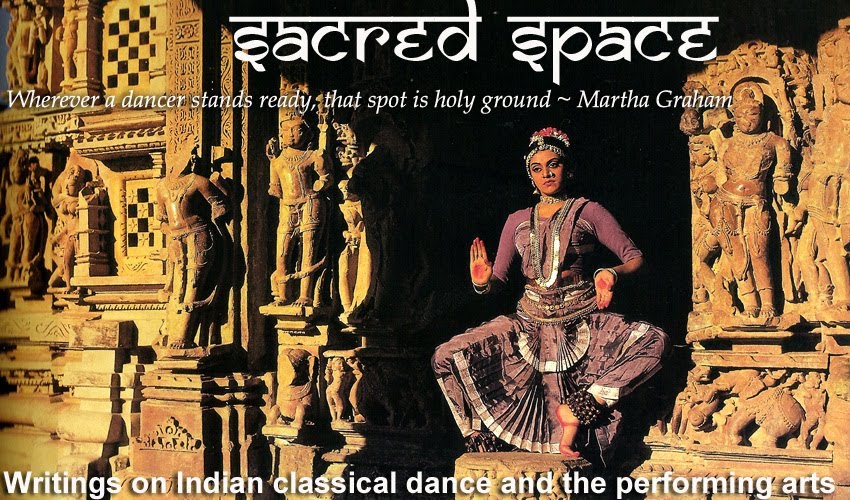

Many of India’s classical dance traditions originated in the temples, where dance was presented as a sacred ritual offering to the deity. Eventually Indian classical dance moved from these sacred spaces to performance venues, where it is performed today as entertainment to large audiences. Meanwhile, the temple has become a popular scenic backdrop for dance festivals like Khajuraho, Chidambaram and Mukteshwar.

But in a small, scenic temple in Rang Bagh on the outskirts of Hyderabad, in India’s southern state of Andhra Pradesh, the ritual and ceremonial dances which were once performed by temple dancers known as saanis or bhogams have been revived and reintroduced as a part of worship during the temple’s annual Brahmotsav celebrations. These dance rituals have been restored by the temple authorities through the active collaboration of renowned dancer Swapnasundari, who after making a name for herself as a Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi dancer, dedicated herself to learning and reviving the dance of the Telugu-speaking regions, which is known today as Vilasini Natyam.

The opportunity to reintroduce these ritual dances as a part of temple worship seemed destined to happen. While performing at a dance festival in Kottakkal, Kerala, Swapnasundari explained to the audience that a ritual form of the dance Vilasini Natyam had been performed in the temples of South India. Sitting in the auditorium was Mr Sharad B Pitti, the chairman and managing trustee of the Sri Ranganathaswamy temple in Rang Bagh. After the performance, he told Swapnasundari about his wish to revive the traditional rituals of the temple, including the dance rituals. “We would go to the temple every year for the Brahmotsav celebrations but the festival had shrunk from what it once was and should be,” he explained. “It was important for me that the rituals should be done in the right way and that justice be done to them. Since dance was an integral part, we had to include it to make the festival complete. I invited Swapnasundari to Rang Bagh because we were interested in reviving dance as part of the temple rituals.”

For Swapnasundari, this opportunity must have seemed like a gift from the gods: “I was eagerly waiting to dance the rituals in their original setting and context,” she said, “rather like a professor of chemistry waiting to find the appropriate laboratory where his or her wonderful formula could be applied in practice! But no temple came forward before the Rang Bagh trustees did.” This opportunity to reinstate and perform the ritual dances of Vilasini Natyam in a temple setting seemed serendipitous and almost a natural result of her efforts to research, document and teach this dance which was once in danger of being forgotten.

What followed was a long process of research and investigation to piece together the rituals in order to be able to reproduce them as authentically as possible. Mr Pitti described the process: “We looked through ancient texts and heard there was a man who had a few books on these rituals. We managed to contact him and he let us photocopy them. They were in Sanskrit and Telugu. Swapnasundari worked very closely with the temple priests to identify and recreate these rituals. What we have now is a refined and filtered version which is the result of a long process.” With great effort, Swapnasundari even managed to contact the daughter of a temple dancer who had been consecrated to this temple. It took much pleading and insistence but she eventually agreed to come to the temple and show Swapnasundari the rituals her mother used to perform.

Using these references and inputs, Swapnasundari was able to identify the dance rituals which were once performed by the temple dancers of Sri Ranganathaswamy temple. These were first reintroduced in 1996 during the temple’s Brahmotsav celebrations, choreographed and performed by Swapnasundari. Today, she and her disciples take turns performing the ritual dances during the eight days of the annual festival which usually falls in February (see below for the 2013 dates).

The Sri Ranganathaswamy temple in Rang Bagh is the only temple where ritual dances are performed as part of worship today. Swapnasundari teaches Vilasini Natyam free of charge so that this tradition can continue. “This is my way of giving back to the temple an aspect of the art which has been taken away from it. I give free classes in the temple-ritual dances of Vilasini Natyam to those who value my sentiment and offer what they learn as service to the temple once a year.”

For the dancers performing these age-old rituals, it is a special experience which goes far beyond a stage performance. “It is a Seva (service) not a performance,” feels Purva Dhanashree. “It’s part of something bigger. On stage it’s all about you. Here you’re just a dot in the pattern. It’s an inner journey.” Anupama Kylash echoes this sentiment: “It’s an internalised experience. I address myself to Him; it’s a dialogue with Him in my thoughts.” Sanjay Kumar Joshi is the only male dancer performing these ritual dances. “For me it’s a divine experience. I perform the dance only for God,” he says. “We want the dance back in the temple, in its context. There are no consecrated temple dancers here, so we perform these sacred ritual dances.”

A description of some of the dance rituals:This article was published in the September 2012 issue of Avantika magazine.The first daily ritual is the Balabhogam when the first food offering of the day is made to the deity. The temple dancer invokes the deity with a hymn called Choornika followed by a Pallavi, an item of Nritta, or pure dance. At 11am and 8:30pm, before the temple idols leave the temple on a palanquin, Baliharanam is performed, followed by the Pallaki seva when they are taken outside the temple, and the Kumbha Arathi and Heccharika on their return.

During Baliharanam, the Ashta Dikpaalakas, the guardian deities of the eight directions, are invoked in a ritual where each deity is asked in turn to provide protection in preparation for the journey outside the temple. After invocations to Brahma and Garuda, the priests, dancers and musicians move in a clockwise direction around the temple, pausing at each of the eight points which are clearly marked by small raised platforms. Starting to the east, Indra is the first guardian-deity to be invoked followed by Agni, Yama, Nirrti, Varuna, Vayu, Kubera and Isana. At each of the eight points, the priests chant prayers in sing-song unison, followed by a loud rhythmical introduction of the Tavil and the Nattuvangam before the singer and flutist join in and the dance begins. Swapnasundari has reclaimed all the obsolete Talas related to this ritual and re-incorporated these into the chorography of this ritual.

With the invocations to the Ashta Dikpaalakas complete and their protection of the temple ensured, the palanquin moves out of the temple compound in a procession. The procession stops on the way, so that devotees can offer their prayers and offerings. At each halt, the dancer dances to a verse of a devotional hymn. By the time the procession completes its journey, an entire song or set of songs would have been completed. This ritual is called Pallaki Seva.

Before re-entering the temple, the palanquin stops just outside the main doorway for the Kumbha-harathi. The temple priest lights a lamp which is placed in a pot. Accompanied to the music of a Mallari, the dancer takes the pot and performs Arati before the deity and then walks around the palanquin. This is an act of purification before it re-enters the temple.

This is followed by the singing of a Heccharika. Through mimed movements, the dancer requests the deities to re-enter the temple with caution as ‘undesirable elements’ may have entered the temple in their absence. At the same time she warns these negative elements to leave the temple premises.

These are the three rituals performed daily. During the Abhisekam (sacred bathing) and Kalyanam (wedding ceremony) of Sri Ranganathaswamy and Maha Lakshmi, other dances are also performed.

This year, Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple celebrates its Brahmotsavam from February 17 to 24, 2013. The dance rituals take place every morning and evening until February 22nd.

In 2014, the Brahmotsavam will take place from February 7 to 11.

Address: Sri Ranganathswamy temple, Rang Bagh, Nanakaramguda, Hyderabad