The title promises to titillate. And it does. But this collection of nine short stories by Gitanjali Kolanad is not only about a young woman’s coming of age but also a candid glimpse into the world of a dancer. The stories are based on her experiences living in the Madras of the 1970s where she studied Bharata Natyam at Kalakshetra, and later during the 1980s when she returned to India as a mother and settled in Delhi.

The first-person narrative is candid and personal, daring and bold, which makes Sleeping with Movie Stars a refreshing and often amusing read. The theme which runs throughout the book is one of self-exploration. A young woman is sent to India by her parents, who hope that such a drastic move will cure her rebellious streak. This is where her artistic journey and voyage of discovery begins. It is in India that she discovers her artistic calling. She readily embraces her new world and all it has to offer. She dares to test limits and move beyond boundaries. She is also forced to examine her cultural identity in a place where she is both an insider, through her Indian heritage, and an outsider – because she was born and brought up in Canada. Released in January 2011 by Penguin, Sleeping with Movie Stars is Kolanad’s second book and first work of fiction. She is also the author of Culture Shock India which is part of the Culture Shock series of cultural guides. The author lives in Toronto, Canada where she teaches kalaripayattu.

Released in January 2011 by Penguin, Sleeping with Movie Stars is Kolanad’s second book and first work of fiction. She is also the author of Culture Shock India which is part of the Culture Shock series of cultural guides. The author lives in Toronto, Canada where she teaches kalaripayattu.

When I met with the author, she told me how the book came about, explained how dance inspires her writing process, her memories of Kalakshetra in the 1970s, and her artistic journey.

What was the impetus to write the book?

I wanted to write about dance and what it’s like to be a dancer. Dancers don’t write about their work, while writers write about writing all the time. There are so many books about writers, painters and musicians. But few books about dancers. I certainly didn’t know when I started dancing that this was what it was going to be like and that I was going to get to 50 and suddenly look behind me and have nothing to show. You do a performance and if nobody writes about it or if it’s not reviewed, the next day it’s as if the performance never existed, except in the minds of the people who saw it. While with other art forms like painting, you still have your painting and you can show it to someone. Especially as I came towards the end of my dance career, I kept feeling this very strongly. I have nothing to show of my work because if it’s on video it’s not the work – it’s only a kind of pale shadow of the work. That was the main impetus, to be able to talk about dance. If you’re a dancer, it’s really something that you do all the time but I don’t think other people understand the kind of art form that dance is.

Is the book a true-to-life memoir?

There is this process that happens when you start writing a story. As soon as you start to structure it, it stops being accurate and factual. The book is not a memoir because it had to be fictionalised in a sense. Not because I wanted to hide anything but because the process of making a story out of what goes on in your life is a process of fictionalising. Even memory is a form of fictionalising.

I had always written journals but I didn’t know how to write. So I read a lot of books on how to write and the process of writing, and I kept writing but nothing was coming together. I couldn’t figure out how to make a story work. Since I was a dancer what I decided to do was try to structure it like a margam. It’s just one of those absolute facts of life that structure helps creativity, it doesn’t hinder it. When you force yourself to use a structure, it’s often helpful because by making constraints for yourself you actually enhance the creative process. So I thought ‘OK, I know how to do an alarippu, so I’ll make a story that’s like an alarippu.’ The first story, ‘Sleeping with Movie Stars’, starts with a motorcycle going this way and then that way because I wanted to find a way to do the eye movement that starts the alarippu.

The second story, 'The American Girl', which won the CBC Literary Award, was about another incident which just remained in my memory. I wanted to write about it and I couldn’t figure out how to do it. But once I had the first story, I had figured out a method that would work for me. So the second story is a jatiswaram, but the structure is something which is deeply buried in it. It’s not something that’s strikingly obvious. The one that’s called 'Tala' is based on the varnam and it changes time and speed. I tried to make it my most ambitious story. It was a challenge and a lot of fun too because it allowed me to think about the dances more deeply: What is the structure of the varnam, and what is it all about? So I think it clarified a lot of things for me which I wasn’t thinking of consciously when I was dancing the varnam.

I wanted to take what came out of me, what came out of my own experience and that’s one reason I stuck to the autobiographical voice, the 'I', for all the stories because I wanted them to be linked to the identity of the artist. And yet the dancer on stage is not the person. She becomes someone else. That’s what’s so wonderful about being on stage. The dance allows a transformation to take place.

Tell me about your dance journey.

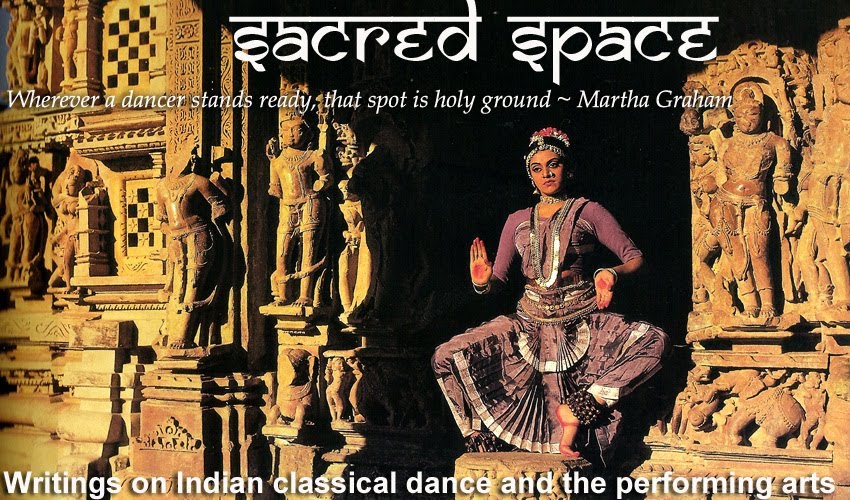

I always thought I was going to be an artist. It sounds funny but I just felt that. Because I didn’t want to get married and have kids – so I thought that’s how you get out of doing all that stuff – by being an artist. Because my name is Gitanjali, I had a fantasy of going to Shantiniketan. It was my father who took me there. I had run away from home so he thought he’d take me to India for a while. I was 16. Once I got to India, he took away my passport and told me I wasn’t going back to Canada. Indian parents are like that. At that time – it was 1970 – Shantiniketan looked to me like a dead place. It was more like a museum than a living institution. And I remember thinking, ‘No, this is not where I want to be’ and left. Much later I found out that there were actually a lot of exciting things going on there. (Left: the author in Madras in 1973.)

I always thought I was going to be an artist. It sounds funny but I just felt that. Because I didn’t want to get married and have kids – so I thought that’s how you get out of doing all that stuff – by being an artist. Because my name is Gitanjali, I had a fantasy of going to Shantiniketan. It was my father who took me there. I had run away from home so he thought he’d take me to India for a while. I was 16. Once I got to India, he took away my passport and told me I wasn’t going back to Canada. Indian parents are like that. At that time – it was 1970 – Shantiniketan looked to me like a dead place. It was more like a museum than a living institution. And I remember thinking, ‘No, this is not where I want to be’ and left. Much later I found out that there were actually a lot of exciting things going on there. (Left: the author in Madras in 1973.)

My father left me at my grandmother’s place in Trichy and then went back to Canada. While I was there, I saw an article about Kalakshetra in Femina magazine. And I still remember thinking, ‘That’s where I want to go.’ I thought I would study painting there. But as soon as I got to Kalakshetra I could see that the only thing that made sense was to study either music or dance. At the audition there was Jaya teacher and Sharada teacher and they asked me to sing something. I couldn’t think of what to sing because I couldn’t sing to save my life! So I sang Blowing in the Wind – the Dylan song. That was the only thing I could think of! I sang one verse of that and they said, “OK that’s enough.” Then they asked me to “do something.” I didn’t know anything about Indian dance so they asked me to do thatt adavu. So I did, and they said, “OK fine. Join.” I stayed at Kalakshetra for four years. But I didn’t get my diploma because in my fourth year I left and went to study with guru A.K. Lakshman.

Who were your contemporaries at Kalakshetra at the time?

Leela Samson was a postgraduate at the time and Subhalakshmi Barua, who later married Amjad Ali Khan, was also studying there. They were both in the postgraduate section. There was the Assamese dancer Indira PP Bora. And my contemporaries, those who were in the class with me: there was Krishnakumari and Renuka. They don’t dance anymore. I find it sad because I was the worst in my class and I’m the only one who’s still dancing! Except Thomas, who’s still at Kalakshetra. And there was this girl who was a very beautiful dancer who danced in all the Kalakshetra dance dramas. She was made for dance. Rukmini Devi adored her and loved her dancing. Her name was Shanta Devi. She came during my first or second year and she went straight into third year. They never did that at Kalakshetra because no matter how much dance you already did, they wanted you to learn the Kalakshetra style, but Shanta went straight into third year. She was an amazingly good dancer. Rukmini Devi put her into dance dramas right away. She played Radha in a Gita Govinda production. I don’t know what happened to her. I think she just went off and got married. This was a thing that happened all the time.

What was Kalakshetra like?

I try not to wax nostalgic about it because it’s really easy to get into that mood of feeling ‘Oh yeah, it was wonderful’. But it wasn’t. The teaching was, in my opinion, terrible. I’m sure Leela Samson has fixed that now. I don’t think the teachers really knew what they were doing. Just because you know how to dance doesn’t mean you know how to teach and the Kalakshetra style came about through a number of misunderstandings. It’s not like you grew up in the dance style and you got the form into your body and really understood it. Rukmini Devi saw it from the outside and then she had to imagine it and reproduce it – and she misunderstood it. For example, at Kalakshetra they would say “Sit! You’re not sitting enough!” And then you’d be leaning forward and then pushing your torso back and you’d have this incredibly strange position while trying to put your arms out at the same time. There’s strain everywhere, so you don’t understand what’s going on and they want you to get your feet out more. As a dancer you could get into so many terribly bad habits. If it came to you naturally, fine. Like for Shanta or Leela, it seems to have come very naturally to them. But if you’re like me and things didn’t come naturally then everything that Kalakshetra did was wrong. It was a misunderstanding. What I realised is that forcing people into a certain aesthetic didn’t really work. (Above: At Kalakshetra, 1973.)

I try not to wax nostalgic about it because it’s really easy to get into that mood of feeling ‘Oh yeah, it was wonderful’. But it wasn’t. The teaching was, in my opinion, terrible. I’m sure Leela Samson has fixed that now. I don’t think the teachers really knew what they were doing. Just because you know how to dance doesn’t mean you know how to teach and the Kalakshetra style came about through a number of misunderstandings. It’s not like you grew up in the dance style and you got the form into your body and really understood it. Rukmini Devi saw it from the outside and then she had to imagine it and reproduce it – and she misunderstood it. For example, at Kalakshetra they would say “Sit! You’re not sitting enough!” And then you’d be leaning forward and then pushing your torso back and you’d have this incredibly strange position while trying to put your arms out at the same time. There’s strain everywhere, so you don’t understand what’s going on and they want you to get your feet out more. As a dancer you could get into so many terribly bad habits. If it came to you naturally, fine. Like for Shanta or Leela, it seems to have come very naturally to them. But if you’re like me and things didn’t come naturally then everything that Kalakshetra did was wrong. It was a misunderstanding. What I realised is that forcing people into a certain aesthetic didn’t really work. (Above: At Kalakshetra, 1973.)

Kalakshetra produced Yamini Krishnamurthy, the Dhananjayans, AK Lakshman… But other than Yamini Krishnamurthy there was no remarkable dancer until Leela Samson came along and I think she came into her own once she left Kalakshetra. If she had stayed there she would have been nobody. She left and found her own way. She’s an amazing teacher. When I moved to Delhi she was teaching there and I watched some of her classes and she was the opposite of Kalakshetra. If you had a class with her she would do all the adavus with you. I really do think that the people who stayed at Kalakshetra didn’t really grow... It produced a mould.

Your book is dedicated to ‘guruji’. Tell me about him.

My guru, Nana Kasar, lived for his students. He absolutely wanted you to be the best you could possibly be, whether you ever made it on to the stage, or not. Because to get yourself onto the stage is very difficult and you can give your life over to doing that, or you can give your life over to being a dancer. He made it seem like there was a point to the process, in your own development, that had everything to do with the work we were doing together in the class, and nothing to do with being on the stage. He was trying to make you perfect, and he and you were in it together.

Previously I had studied with the Dhananjayans and with Professor CV Chandrasekhar in Baroda. I also learned Kuchipudi with Vempati Chinna Satyam. At that time it was considered very bad form to change gurus and styles. People didn’t like that I did that. Later I studied with Kalanidhi Narayan. She is another amazing teacher. I think people talk about her in all kinds of very respectful ways but they don’t really get to the heart of what she does. She’s another one of those teachers who’s there to make you undergo a spiritual transformation. The dance is what is important to her. These are true gurus and they give away what they have. She teaches you how you have to examine a padam to get at its essence. So you shouldn’t need to go to her to learn another padam or another javali, you should be engaging in that process with each padam and javali yourself. And she would say to me, “I don’t know why students keep coming back. I’ve given them the secret.”

I had my arangetram in Toronto around the time when I was 22 or 23. Then I came back to India. I started with Guruji when I was about 30 and I had already realised that I wasn’t going to be a great dancer, that that wasn’t in the cards for me. It was very difficult to accept that I didn’t have the gifts, the discipline, whatever it was. So at that point I tried to give up dancing – but it didn’t work. It was so much a part of me. And that’s when I went back to Guruji. He said, “It doesn’t matter. You don’t have to be a great dancer. It is the process that is important.”

I’ve always thought that learning a great Tanjore Quartet margam from beginning to end is like possessing a great painting by a master artist. Except instead of hanging it on the wall, you have it in you. To work on that kind of masterwork with a teacher who is able to reveal every nuance is a profound experience. That was a great year for me when Guruji and I started to work together in a serious way on something that had no other reward than the work itself.

How did you get into kalaripayattu?

I saw kalaripayattu in Delhi for the first time during a theatre festival. They advertised that they were doing a workshop and I was the only one who showed up! Gopinath, the teacher for K Narayana Panicker’s theatre troupe was there. Now Bharata Natyam dancers are more into physical training but at the time they weren’t. I started with Gopinath and then I went to Kerala with my two kids to study it more intensely. Today I teach kalaripayattu in Toronto.

What’s interesting is that kalari is not an elite art form. If you go to a village in Kerala, everyone does kalari. You don’t know what caste or religion they are or how much money they make. In the kalari you’re all equal and then you walk out and see that one of the guys who’s really wonderful at kalari is actually an auto-rickshaw driver. What a contrast to go from dance classes in Madras where all the girls come in their cars, to business men and auto-rickshaw drivers in the same kalari class. It’s incredibly egalitarian in that way. By that time I had completely lost my interest in gods and goddesses and all of that kind of thing. It didn’t interest me anymore. Kalari doesn’t have any of that.

How will people react to your book in India, especially the sensual parts?

Well I’m really curious to see. I’m not shy about saying that a lot of the book is based on what happened to me. Everything in the first story describes an actual experience, while leaving out what's extraneous. It was absolutely unheard of to live on your own at the time. But Kalakshetra didn’t say anything about it. They didn’t try to stop me from coming to class. Everyone knew I was living on my own. They didn’t say anything or try to moralise me in any way either, but the neighbours did. I was living with a Sri Lankan girl and there was also this American girl who was studying veena at Kalakshetra. Our neighbours had a problem with the three of us. The men in the village thought we were prostitutes; they had no other conception of three women living on their own.

When I first came to India I thought that everyone was repressed and that nobody had sex. But then what I realised was that nobody talked about it but all kinds of things were going on. There were some things that didn’t make it into my book. So I slowly began to realise the repression is just on the surface, you’re not supposed to talk about it but all kinds of stuff is going on, just like in the West.

Read the first short story in the collection here.

Visit Gitanjali Kolanad's website here.

Photos courtesy of the author.